My college friend Katie, an avid knitter, once wisely foretold that I would like knitting because it was so mathematical.

She was right.

Since starting to knit more seriously a year ago, not only have I appreciated the mathematics of knitting, I’ve seen many interesting parallels with programming. So without further ado, here is a yarn about knitting and computer science.

Binary.

Knitted fabric is binary. Just like the 0s and 1s of computerese, there are two basic stitches in knitting: the knit stitch and the purl stitch. On the “right side” of the fabric, the knit is a flat loop, the purl is a bump.

Just as computer code is, at its core, repeated patterns of 0s and 1s, most classic patterns are simply different combinations of knit and purl stitches (repeated k1,p1 is ribbing, all knit stitches on the same side is stocking stich).

I oversimplify - there’s more to it than that - but you can get pretty far with knitting interesting textures and patterns, just knowing these two stitches

(Million dollar idea: a spy movie where the plot hinges on Secret Agent Knitting Nelly sneaking behind enemy lines wearing a sweater knitted from code (knits = 0s, purls = 1s), that then has to be unraveled (literally) and turned back into a program.)

Operations.

Besides knits and purls, we also have increases and decreases. Beyond texture, we can also think about overall shape, based on number of stitches in a row. You could think of each row as an “index” variable, that’s constantly being updated (incremented + decremented) by increase and decrease operations.

Once you know this, it’s not that difficult to make different shapes. The basic premise of making a hat is to start with a certain number of stitches in the round, and then, at some point, regularly decreasing. We can thus soup up our basic binary stitches with literal addition and subtraction to actually make something meaningful.

In Elizabeth Zimmerman’s Knitter’s Almanac, she opines on the mathematics of increases while describing how to knit a circular shawl:

“Have you begun to see the well-known geometric theory behind what you have been doing? … It’s Pi; the geometry of the circle hinging on the mysterious relationship of the circumference of the circle to its radius. A circle will double its circumference in infinitely themselves-doubling distances, or, in knitters’ terms, the distinace between the increase rounds, in which you double the number of stitches, goes 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96 rounds, and so on to 192, 394, 788, 1576 for all I know.”

Her wise conclusion is:

“Theory is theory, and I have no intention of putting it into practice, as I do not plan to make a lace carpet for a football field.”

Code.

At this point, it’s hopefully clear that knitting patterns are like a program,

where the input is a single string of yarn (almost like streaming text

from standard input) and the output is some kind

of knitted object. The compiler/interpreter is, of course, the knitter.

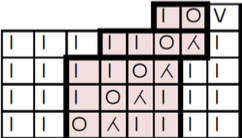

This gets especially computer-sciencey when your “program” or instructions are written as a chart.

Charts bear more than a passing resemblance to ye-olde punch cards of yore, indicating what “operation” (stich) should be performed at each stage of the row.

While loops.

No matter what kind of directions you’re using (chart or written), it’s very common to have a while loop. Frequently, patterns will have a set of unique stitches, then a repeated part of the pattern (the loop), then an ending part of the pattern.

In chart, written out + programming, this would look like (from a shawl I’m currently knitting):

| Chart | Written | Program |

|---|---|---|

|

k1 * yo sl k1 * k1 |

stitches_remaining = 128 k1 stiches_remaining -= 1 WHILE (stiches_remaining > 1) DO yo s k1 stitches_remaining -=2 DONE k1 |

So you can see in the chart, the highlighted box indicates the body of the loop; in the written instructions, the loop body is surrounded by asterisks.

Test driven development.

One of the most important ways that knitting is like coding? Test driven development.

Say what?

In the world of knitting, there’s something called gauge. Gauge is the size (in inches or centimers) of a 10 stitches x 10 rows (or some other n x n) piece of knitting, based on your yarn, needles, and personal knitting tension. When knitting from a new pattern, it’s recommended to knit out a test piece called a “swatch” to check if your gauge matches that recommended by the instructions. If you’re like me and are always over, you can adjust by using smaller needles or fewer stitches, depending on the pattern.

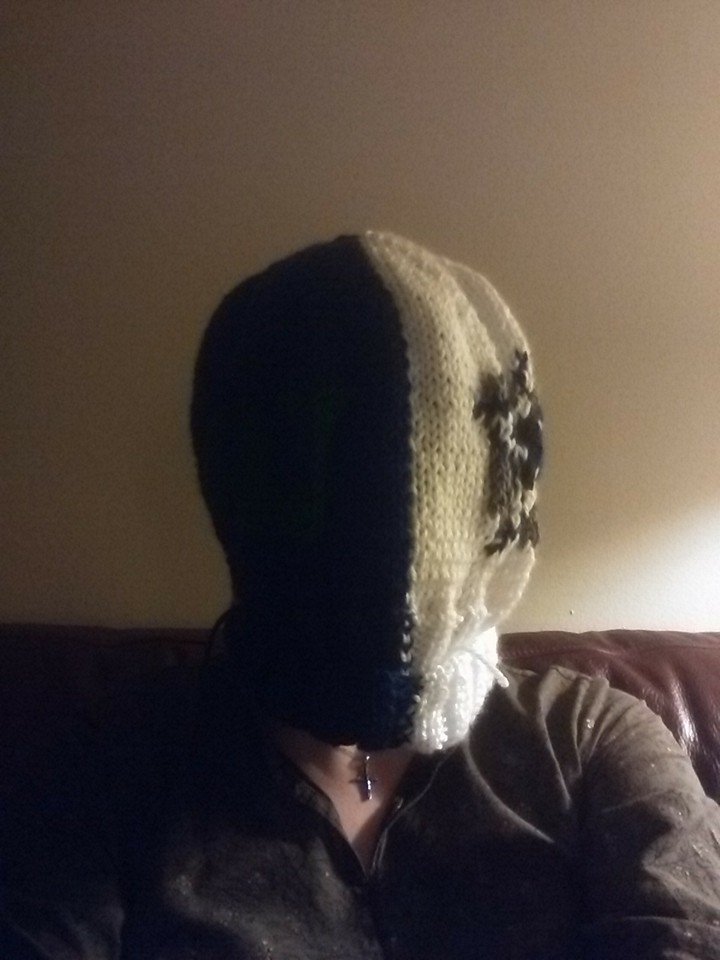

Like writing tests for software, I pooh-poohed the idea of knitting a swatch to check my gauge until the month I knitted a hat that was so big it literally covered my head.

Now, if I’m going to knit anything that needs to be a certain size (for example, to fit a normal human being), I dutifully knit my swatch and make sure I’ll be able to wear the finished project. Test before development.

Code comments.

Finally, when knitting, it is important to comment on your pattern, especially if you’re supposed to be creating two things that match (e.g. slippers or mittens). As someone who frequently improvises on patterns, I am the queen of thinking, “I’ll remember where I shortened that row, instead of following the pattern as written” – HA. No such thing. I now make sure I always have a pen on me when I knit, because at the very least, I can check off which row I just finished, enabling me to start again in the right place.

Post Script

For those disappointed by the lack of math in this blog post, see this article sent to me by my roommate. (I’d like to crochet the Lorenz manifold someday.) See also the mathematical knitting page of sarah-marie belcastro.