Motivation and Demotivation

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 45 minQuestions

Why is motivation important?

How can we create a motivating environment for learners?

Objectives

Identify authentic tasks and explain why teaching using them is important.

Develop strategies to avoid demotivating learners.

Recognize and overcome imposter syndrome in yourself and your learners.

In the morning we covered some educational research and how we can apply it to teaching Carpentries workshops. Part of this afternoon will cover another important aspect of being a Carpentries instructor: fostering a positive learning environment.

This section discusses typical ways that learners are motivated (and can be demotivated!) and provides practice opportunities for you to become confident in motivating your learners.

Creating A Positive Learning Environment

Creating a positive learning environment is an important first step to setting the stage for learner success. As instructors, it is crucial to establish the workshop setting as a safe space for learning. Establishing a safe space for learning is a combination of many factors:

- Presenting the instructor as a learner. Admitting that you don’t know everything is part of showing that it is acceptable to make mistakes, and encouraging a growth mindset in learners (we’ll talk much more about growth mindset in a later lesson). Using participatory live coding, our chosen method for teaching concepts, is very useful for this reason. It is common to make errors while coding. When handled transparently, these errors can be very instructive for novice learners.

- Establishing norms for interaction. This can be done by having, discussing, and enforcing a Code of Conduct or by having rules of interaction such as ensuring turn taking in discussions, possibly by passing around a talking stick, or by encouraging quieter people to contribute.

- Encouraging learners to learn from each other. Acknowledge that some of the material can be difficult and that they will learn more working together. Asking more advanced learners to help beginner learners is a good way to maximize learning for both.

- Acknowledging when learners are confused. Understanding why learners are confused provides useful feedback for instructors. We use formative assessments to pinpoint learners’ misunderstandings. Acknowledging that their misunderstandings are valid is also key to encouraging a growth mindset.

Teach Most Useful First

One way to build a positive classroom environment is to create a space that cultivates and encourages learners’ motivations.

People learn best when they care about a topic and believe they can master it. Many scientists might know vaguely the value of programming but find it intimidating, and struggle with how to get started. This presents us with a problem because believing that something will be hard to learn often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

We have therefore adopted a “teach most immediately useful first” approach. We try to have learners do something that they think is useful in their daily work within 15 minutes of starting each lesson. This not only motivates them, it also helps build their confidence in us, so that if it takes longer to get to something they find useful in a later topic, they’ll persist with the lesson.

To do this, we as instructors need to go through the work of identifying what to teach first (or at all!). Imagine a graph whose axes are labelled “mean time to master” and “usefulness once mastered”. Everything that’s quick to master, and immediately useful should be taught first; things in the opposite corner that are hard to learn and have little near-term application don’t belong in our workshops.

Another way to think about the graph shown above is “authentic tasks.” An authentic task is exactly what it sounds like – a real task performed by someone doing their work. If you can identify authentic tasks from your own work that could be useful to others, these examples will be highly motivating.

Authentic Tasks: Think, Pair, Share

Think about some task you did this week that uses one or more of the skills we teach, (e.g. wrote a function, bulk downloaded data, built a plot in R, forked a repo) and explain how you would use it (or a simplified version of it) as an exercise or example in class. Pair up with your neighbor and decide where this exercise fits on a graph of “short/long time to master” and “low/high usefulness”. In the class Etherpad, share the task and where it fits on the graph. As a group, we will discuss how these relate back to our “teach most immediately useful first” approach.

This exercise and discussion should take about 10 minutes.

Actual Time

Any useful estimate of how long something takes to master must take into account how frequent failures are and how much time is lost to them. For example, editing a text file seems like a simple task, but most graphical editors save things to the user’s desktop or home directory. If people need to run shell commands on the files they’ve edited, a substantial fraction won’t be able to navigate to the right directory without help. If this seems like a small problem to you, please revisit the discussion of expert awareness gap.

Other Motivational Strategies

In addition to teaching things that will make our learners’ lives easier and focusing on authentic tasks, there are a number of other strategies we can use to motivate learners.

Strategies for Motivating Learners

How Learning Works by Susan Ambrose, et al., contains this list of evidence-based methods to motivate learners.

In groups of two or three, pick three of these points and briefly describe in the Etherpad how we can apply these strategies in our workshops.

- Strategies to Establish Value

- Connect the material to learners’ interests.

- Provide authentic, real-world tasks.

- Show relevance to learners’ current academic lives.

- Demonstrate the relevance of higher-level skills to learners’ future professional lives.

- Identify and reward what you value.

- Show your own passion and enthusiasm for the discipline.

- Strategies to Build Positive Expectations

- Ensure alignment of objectives, assessments, and instructional strategies.

- Identify an appropriate level of challenge.

- Create assignments that provide an appropriate level of challenge.

- Provide early success opportunities.

- Articulate your expectations.

- Provide rubrics.

- Provide targeted feedback.

- Be fair.

- Educate learners about the ways we explain success and failure.

- Describe effective study strategies.

- Strategies for Self-Efficacy

- Provide learners with options and the ability to make choices.

- Give learners an opportunity to reflect.

This exercise and discussion should take about 5 minutes.

Provide an Example

Insert a personal story here about how you establish value in the classroom.

Or, insert an example story about establishing value, which goes like this:

“In the SWC Unix “Finding Things” episode, a haiku is used to to teach grep. This is a great didactic tool, but it can be hard for learners to see how it applies to research. After the didactic example, I connect my bioinformatics users with domain-specific examples by showing a list of one-line unix commands consisting of

grep,sort,head, anduniqto explore biological sequence data. This emphasizes how they can apply what they learned with haikus to real bioinformatics research problems.”

Brainstorming Motivational Strategies

Think back to a computational (or other) course you took in the past, and identify one thing the instructor did that motivated you. Pair up with your neighbor and discuss what motivated you. Share the motivational story in the Etherpad.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Not Just Learners

What’s missing from this list is strategies to motivate the instructor. As we said in the introduction, learners respond to an instructor’s enthusiasm, and instructors need to care about a topic in order to keep teaching it, particularly when they are volunteers.

Why Do You Teach? (Optional)

We all have a different motivation for teaching, and that is a really good thing! The Carpentries want instructors with diverse backgrounds because you each bring something unique to our community.

What motivates you to teach? Write a short explanation of what motivates you to teach. Save this as part of your teaching philosophy for future reference.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

How Not to Demotivate Your Learners

Motivation can go both ways. Besides using strategies to motivate learners, one of our additional challenges as instructors is to not demotivate participants through our words or actions. None of us goes into a workshop with the intention of creating a hostile environment or making the learners hate the tools we’re teaching, but we can all accidentally do just that if we don’t pay attention to what we say and how we interact with our learners. We’ll discuss some common demotivators and help you develop strategies for avoiding them.

Brainstorming Demotivational Experiences

Think back to a time when you were demotivated as a student (or when you demotivated a student). Pair up with your neighbor and discuss what could have been done differently in the situation to make it not demotivating. Share your story in the Etherpad.

If time, what themes do you see among the stories? What are positive actions you could take to avoid these?

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Things You Shouldn’t Do in a Workshop

- Tell learners they are rubbish because they use Excel and/or Word, don’t modularize their code, etc.

- Say negative things about Windows and praise Linux, e.g., say that the former is for amateurs.

- Criticize GUI applications (and by implication their users) and describe command-line tools as the One True Way.

- Talk contemptuously or with scorn about any tool. Regardless of its shortcomings, many of your learners may be using that tool. Convincing someone to change their practices is much harder when they think you disdain them.

- Dive into complex or detailed technical discussion with the one or two people in the audience who clearly don’t actually need to be there.

- Pretend to know more than you do. People will actually trust you more if you are frank about the limitations of your knowledge, and will be more likely to ask questions and seek help.

- Use the J word (“just”) or other demotivating words we talked about in a previous lesson. These signal to the learner that the instructor thinks their problem is trivial and by extension that they therefore must be stupid for not being able to figure it out.

- Take over the learner’s keyboard. It is rarely a good idea to type anything for your learners. Doing so can be demotivating for the learner (as it implies you don’t think they can do it themselves or that you don’t want to wait for them). It also wastes a valuable opportunity for your learner to develop muscle memory and other skills that are essential for independent work.

- Feign surprise. Saying things like “I can’t believe you don’t know X” or “You’ve never heard of Y?” signals to the learner that they do not have some required pre-knowledge of the material you are teaching, that they don’t belong at the workshop, and it may prevent them from asking questions in the future. (For more on this see the Recurse Center’s Social Rules).

It can be difficult to avoid these demotivators entirely. Some people are so used to making fun of Windows-users with their friends, or talking about how terrible Excel is that they initially fail to realize they’re doing it while teaching. Teaching yourself to avoid these types of comments takes practice, but is well worth the effort. No one likes to be made fun of, and talking badly about people who use GUIs, or who aren’t writing their thesis in LaTeX is unlikely to make them excited about learning your favorite scripting language.

Systemic and Psychological Demotivators

As instructors, we can learn to avoid talking disparagingly about our learners’ choice of text editors and levels of technical knowledge. There are other factors, however, that contribute to demotivation, some of which are either systemic, or built into our psychological makeup as human beings. We can’t always control these demotivators - often they come from outside classrom - but we can be aware of them, and take certain actions to lessen their impact by thinking carefully about the language that we use and how we interact with our learners.

Stereotype Threat

One major psychological demotivator is stereotype threat. Reminding people of negative stereotypes, even in subtle ways, can make them anxious about the risk of confirming those stereotypes, in turn reducing their performance. This is called stereotype threat, and the clearest examples in computing are gender-related. Depending on whose numbers you trust, only 12-18% of programmers are women, and those figures have actually been getting worse over the last 20 years. There are many reasons for this (see Margolis and Fisher’s Unlocking the Clubhouse and Margolis’s Stuck in the Shallow End). Steele’s Whistling Vivaldi summarizes what we know about stereotype threat in general and presents some strategies for mitigating it in the classroom.

While there’s lots of evidence that unwelcoming climates demotivate members of under-represented groups, it’s not clear that stereotype threat is the underlying mechanism. Part of the problem is that the term has been used in many ways. Another is that there are questions about the replicability of key studies. What is clear is that we need to avoid thinking in terms of a deficit model (i.e., we need to change the members of under-represented groups because they have some deficit, such as lack of prior experience) and instead use a systems approach (i.e., we need to change the system because it produces these disparities). We can also not highlight people based on their identity with a minority group; for example, it’s not a good idea to say something like “I’m so glad you’re here because we don’t get enough women in programming.” That may sound positive, but draws attention to the stereotype that women aren’t good at programming.

Never Learn Alone

One way to support at-risk learners of all kinds is to ask people to sign up for workshops in small teams rather than as individuals when possible. If an entire lab group comes, or if attendees are drawn from the same (or closely-related) disciplines, everyone in the room will know in advance that they will be with at least a few people they trust, which increases the chances of them actually coming. Furthermore, if people attend a workshop with their labmates, it’s more likely they will work together to implement what they’ve learned after the workshop has ended.

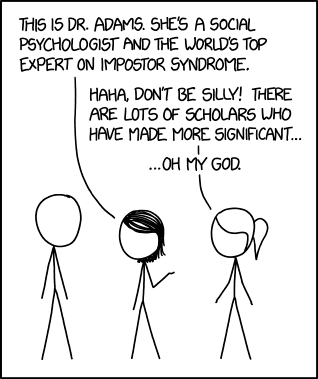

Impostor Syndrome

Another major psychological demotivator is impostor syndrome. Imposter syndrome is the belief that one is not good enough for a job or position, and that one’s achievements are due to luck rather than talent or skill. This is also accompanied by the fear of being “found out”.

https://xkcd.com/1954/

https://xkcd.com/1954/

Academic work is frequently undertaken alone or in small groups but the results are shared and criticized publicly. In addition, we rarely see the struggles of others, only their finished work, which can feed the belief that everyone else finds it easy. Women and minority groups, who already feel additional pressure to prove themselves in some settings, may be particularly affected.

Two ways of dealing with your own impostor syndrome are:

- Ask for feedback from someone you respect and trust. Ask them for their honest thoughts on your strengths and achievements, and commit to believing them.

- Look for role models. Who do you know who presents as confident and capable? Think about how they conduct themselves. What lessons can you learn from them? What habits can you borrow? (Remember, they quite possibly also feel as if they are making it up as they go.)

As an instructor, you can help people with their impostor syndrome by sharing stories of mistakes that you have made or things you struggled to learn. This reassures the class that it’s OK to find topics difficult. Being open with the group makes it easier to build trust and make learners confident to ask questions. (Live coding is great for this: typos let the class see you’re not superhuman.)

You can also emphasize that you want questions: you are not succeeding as a teacher if no one can follow your class, so you’re asking learners to help you learn and improve. Remember, it’s much more important to be smart than to look smart.

The Ada Initiative has some excellent resources for teaching about and dealing with imposter syndrome.

Overcoming Imposter Syndrome (Optional)

Think of a time when learning something was difficult for you, or you made a mistake that seemed silly or embarrassing. Is that task still hard for you? In the Etherpad, describe how you might use this as a motivational story to help your learners overcome their own imposter syndrome.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Accessibility Issues

Not providing equal access to lessons and exercises is about as demotivating as it gets. If you look at our old lesson on Python, for example, you’ll find that the text beside the slides includes all of the narration—but none of the Python source code. Someone using a screen reader would therefore be able to hear what was being said about the program, but wouldn’t know what the program actually was.

While it may not be possible to accommodate everyone’s needs, it is possible to get a good working structure in place without any knowledge of what specific disabilities people might have. Having at least some accommodations prepared also makes it clear that hosts and instructors care enough to have thought about problems in advance, and that any additional concerns are likely to be addressed.

It Helps Everyone

Curb cuts (the small sloped ramps joining a sidewalk to the street) were originally created to make it easier for wheelchair users to move around, but proved to be equally helpful to people with strollers and grocery carts. Similarly, steps taken to make lessons more accessible to people with various disabilities also help everyone else. Proper captioning of images, for example, benefits people with no or limited vision by giving screen readers something to say: but it also makes the images more findable by exposing their content to search engines.

The first step is to know what you need to do. There are a number of good resources for learning about accessibility.

Learning about Accessibility

The UK Home Office has put together a set of posters of dos and don’ts for making visual and web-based materials more accessible for different populations. Take a look at one of these posters and put one thing you’ve learned in the Etherpad.

Note: There are translations available in a number of languages, including Dutch, French, Spanish, Swedish, Portuguese, German, and Chinese.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Accessibility and PDFs

The posters above are in PDF format - which itself can sometimes be inaccessible to people who use screen readers. If you know of a similar resource describing accessibility guidelines that would be more accessible than what’s linked above, open an issue on our instructor training curriculum respoistory here: https://github.com/carpentries/instructor-training/issues

The W3C Accessibility Initiative’s checklist for presentations is a good starting point focused primarily on assisting the visually impaired, while Liz Henry’s blog post about accessibility at conferences has a good checklist for people with mobility issues, and this interview with Chad Taylor is a good introduction to issues faced by those with no or limited hearing.

The second is to know how well you’re doing. For example, sites like WebAIM allow you to check how accessible your online materials are to users with no or limited vision.

The third, and most important, is to involve people with disabilities in decision-making. Our mailing lists are a good place to ask for advice, and updates to our accessibility checklist are always welcome.

What Happens When Accessibility is an Issue? (Optional)

Think of a time when you’ve been affected by, or noticed someone else being affected by issues with accessibility. This may have been at a conference you attended where the elevator was out of service, or maybe a class you were taking relied on audio delivery of content. Describe what happened, how it impacted your (or someone else’s) ability to be involved and what could have been done to provide better accessibility in this case.

This exercise should take about 5 minutes.

Every Little Bit Counts

Looking at people who work with disability and accessibility, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by all the different ways we could make instruction more accessible. Don’t panic. Instead:

- Don’t do everything at once. We don’t ask learners in our workshops to adopt all our best practices or tools in one go, but instead to work things in gradually at whatever rate they can manage. Similarly, try to build in accessibility habits when preparing for workshops by adding something new each time.

- Do the easy things first. There are plenty of ways to make workshops more accessible that are both easy and don’t create extra cognitive load for anyone: font choices, general text size, checking in advance that your room is accessible via an elevator or ramp, etc.

Accessibility Testing

Find the nearest public transportation drop-off point to your building and walk from there to your office and then to the nearest washroom, making notes about things you think would be difficult for a wheelchair user. Now borrow a wheelchair and repeat the journey. How complete was your list of challenges? And did you notice that the first sentence in this challenge assumed you could walk?

Inclusivity

Inclusivity is a policy of including people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized. In computing, it means making a positive effort to be more welcoming to women, people of color, people with various sexual orientations, the elderly, people with physical disabilities, the formerly incarcerated, the economically disadvantaged, and everyone else who doesn’t fit Silicon Valley’s white/Asian male demographic. Lee’s paper “What can I do today to create a more inclusive community in CS?” is a brief, practical guide with references to the research literature. These help learners who belong to one or more marginalized or excluded groups, but help motivate everyone else as well.

Many of these can be applied to our workshops, such as:

- asking learners to email you before the workshop to explain how they believe the training could help them achieve their goals;

- reviewing notes to make sure they are free from gendered pronouns, that they include culturally diverse names, etc.;

- emphasizing that what matters is the rate at which they are learning, not the level of knowledge they had when they started;

- encouraging pair programming; and

- actively mitigating behavior that some learners may find intimidating, e.g., use of jargon or “questions” that are actually asked to display knowledge.

Setting Expectations with the Code of Conduct

Finally, a important way that the Carpentries foster an inclusive, respectful learning environment is our Code of Conduct.

To make clear what is expected, all participants in our workshops are required to conform to the Code of Conduct. Its details are important, but the most important thing about it is that it exists: knowing that we have rules tells people a great deal about our values and about what kind of learning experience they can expect.

We will discuss the Code of Conduct in greater detail tomorrow.

Key Points

A positive learning environment helps people concentrate on learning.

People learn best when they see the utility in what they’re learning, so teach what’s most immediately useful first.

Imposter syndrome is a powerful force, but can be overcome.

Accessibility benefits everyone.